Tags

Books by Gary Chapman, life experiences, Memories, The River Flows Both Ways, Vietnam and Cambodia

Curt Williams was one of the peculiar elder saints of the United Church of Tilton. In 1973, a few months after I arrived there, he gave me a wooden coin with the letters “TUIT” on one side, when I admitted, “I didn’t get around to doing that.” “You’ll never have to say that again,” he responded with a smile.

Over the years the need for that round TUIT has returned many times, especially when a stack of unread material and unfinished projects has piled up. The only advantage of procrastination has been that some items are so outdated they can be filed quickly in File 13.

One such set of files was marked “Selective Service 1964 to 1972.” That file used to seem so significant. I was a volunteer draft counselor with the American Friends Service Committee, talking to dozens of peers who were looking at their options. I was the potential holder of four deferments—student, medical, conscientious objector, and theological student. There had been many letters, reclassifications, and everyone on my draft board knew me. Even when I stopped responding to their letters, they ignored my non-cooperation. The whole extended episode was a time to be forgotten, and I succeeded in forgetting most of it. Twenty years later I discarded the file.

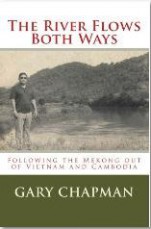

The letters from friends serving in Vietnam was another matter, still on file. I proposed to my wife just before Thanksgiving of 1967, confessing to her that I didn’t know what the war would do to us. We married during the Democratic National Convention in Chicago, so I did not join my fellow members of the Students for a Democratic Society in Grant Park. Our daughter was born immediately after the Kent State killings when University of Chicago students had dug trenches into the empty lot a block from our apartment building. Our son was born in 1973, just after the Paris Accords were signed and America’s soldiers were being withdrawn. When I got around to it, I told myself, I should write something about those times. In 2007 I did, although it took shape around the experiences of my son-in-law and his brother and became the book The River Flows Both Ways.

President George H.W. Bush said in 1988, “No great nation can long be sundered by a memory.” More than fifty years after those days, “The Vietnam War,” the documentary film from Ken Burns and Lynn Novick, finally puts a comprehensive review of that war before the world.

Some psychologists say that we forget things for reasons that are unconsciously hostile. We also postpone forgetting things, remembering certain things with hostility. Is there not a time peacefully to remember, releasing hostility in the creative act of beating swords into plowshares and spears into pruning hooks? Sometimes it takes a while to get around to it. We wait until the lessons we should have learned earlier are repeated before our eyes.